Privilege Of The Rich Over The Evidence: In 2003, Vanity Fair published an article by Vicky Ward entitled “The Talented Mr. Epstein.” Most of it was about Epstein’s finances, business contacts, extravagant living and the mystery surrounding how he made his money. But there was a line tucked into the article that read: “Epstein is known about town as a man who loves women — lots of them, mostly young.”

Journalist Ward could have written much more about Epstein’s predilection for sexually exploiting young girls had Graydon Carter, her editor at Vanity Fair, not gagged her. Carter wouldn’t allow Ward to print allegations that Epstein had tried to sexually seduce two young girls who were sisters (Ward, 2016).

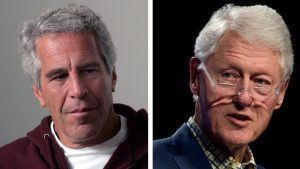

RELATED: Friends of Jeffrey Epstein Participated In Sexual Assualt

Epstein mounted a campaign attacking both Ward and her sources, deluging Carter with a flood of telephone calls from himself and his friends, bullying Carter to suppress the allegations.

Ward later responded in an article in The Daily Beast entitled, “I Tried to Warn You About Sleazy Billionaire Jeffrey Epstein in 2003.” In 2005 Palm Beach police began an 11-month investigation into the comings and goings at Epstein’s mansion. Neighbors had reported many young women arriving at all hours.

Police Chief Reiter recalled that Epstein had probably gotten wind of the investigation since he subsequently sent the department a donation of $90,000. In the beginning of the investigation, Chief Reiter suspected that Epstein was using his mansion for prostitution.

In the Chief’s view, prostitution in private residences wasn’t high on his list of priorities, because he believed the young women coming to Epstein were all adults and that prostitution is common everywhere in America — in other words, not a big deal. But to him, sexual exploitation of minors was a different story.

When the Chief obtained his first testimony from one of the young girls who had been Epstein’s prey, the case against him began to come together when other victims also came forward. The girls knew what they were talking about and told a shocking tale about Epstein’s sexual depravities.

Each girl interviewed told a story whose details of Epstein’s “massage” routine were remarkably the same. In a key interview with Jose Alessi, a former houseman employed at Epstein’s mansion, he verified that girls brought into the house to sexually service Epstein appeared to be 16, 17 or younger.

Another employee testified that his job was to wipe down the vibrators and sex toys (Palm Beach Police Department, 2005-2006). The police also obtained the cell and home telephone records of several more victims and witnesses, and later they were able to access Epstein’s private phone information and flight logs on days when girls were slated to give him massages.

When Reiter determined he had all the evidence that he needed, he presented it to the state attorney, Barry Krischer. However, there was one problem. Krischer himself had been accused of sexual misconduct in 1992, allegedly groping, kissing and otherwise molesting a woman who worked as his legal secretary. Krischer denied the allegations (Patterson, 2016).

The police wanted to charge Epstein with felonies that would have placed him behind bars for years. They had assembled a powerful case for justice to prevail. A red flag was raised when Krischer indicated he had doubts about the credibility of the young women who had given evidence against Epstein.

In the meantime, Epstein’s lawyers went to work drafting their own version of how the prosecutor should handle the case. They basically rewrote the charges and demoted Epstein’s sentence to a mere misdemeanor, or five years of probation and a psychological examination.

After the months of work and the credible evidence that had been assembled, Chief Reiter was furious. In July 2006, a grand jury reached a verdict that outraged the police department, recommending that Epstein be indicted on only one felony count of solicitation of prostitution.

The legal team had whittled Epstein’s crimes down to a prostitution offense because they were aiming for the legal bottom of the penalty barrel.

In the legal pantheon of penalties, reducing a defendant’s sentence to a prostitution charge says a lot about rich clients and well-financed lawyers and how, when caught, they can manage to dial down the sexual assault of women into a more lenient offense for the men involved.

The system separates crimes of commercial sexual exploitation from the severity of other sexual assaults perpetrated against women and girls. After condemning Krischer for not pursuing more serious charges against Epstein, the police chief referred the case to the FBI and the federal prosecutor’s office.

Reiter was hopeful when Alex Acosta, the U.S. Attorney in Miami, took on the case because Acosta had declared that one of his priorities would be prosecuting anyone guilty of sex crimes. Reiter’s optimism was short-lived.

The Miami Herald article that dug deep into Jeffrey Epstein’s sexual abuse of young girls revealed how the justice system consistently failed Jeffrey Epstein’s victims. Journalist Julie Brown identified 80 of Epstein’s victims, four of whom spoke to her on record. The article brought renewed scrutiny to Epstein’s crimes and produced public outrage.

What generated much of the outrage was the corrupt plea deal that Epstein’s lawyers negotiated with Alex Acosta.

In 2008, Epstein walked away from justice with a boondoggle of legal exemptions: pleading guilty to two lesser state prostitution charges, gaining immunity from four federal criminal charges, and stopping a probe into his involvement in an international sex trafficking operation.

As part of the plea agreement, he was required to register as a sex offender, pay restitution to three dozen victims identified by the FBI, and serve 18 months in jail which was ultimately reduced to 13. The plea deal — a non-prosecution agreement — shut down any further FBI investigation into other likely victims and perpetrators.

Instead of being sent to the state prison, Epstein was detained in the more comfortable private wing of the Palm Beach County Jail where he was protected by his own personal body guards from other inmates who might try to enact their own prison justice meted out to sex offenders and pedophiles.

Granted special “work release” privileges to travel to his office six days a week, 12 hours per day, he was allowed to freely come and go from jail. This approval was given in violation of a directive from the Sheriff’s Department that sex offenders are not eligible for work release.

Ultimately, Alex Acosta and the other federal prosecutors bowed to pressure from Epstein’s legal team. As one senator put it, the Department of Justice cut a “sweetheart deal with a sexual predator.” A 53-page indictment against Epstein was sealed and Epstein’s victims were never notified about the non-prosecution agreement.

The agreement violated a federal law stating that crime victims must be informed about plea bargains related to their own cases. As the perpetrators and co-conspirators intended, the cover up would insure that any victims or witnesses would not appear in court to oppose the deal.

More unusual was a provision that “any potential co-conspirators,” who were never identified, would be given immunity. This led to speculation that some very influential men feared that if this indictment was made public, they might be charged as Epstein’s accomplices in crime or as actual perpetrators.

Knowing that he could at any point implicate or blackmail them, they may have joined in buying Epstein the best deal that money could buy. This shameful arrangement was a second pushback for Reiter who had handed the Epstein case over to federal prosecutors when the state attorney had wavered on filing serious charges.

He said: “So many people, primarily the victims, paid so dearly for how this was handled by the government (Mazzei, 2018).” Acosta whined he was the victim of Epstein’s lawyers, calling the plea negotiations a “year-long assault on the prosecution and the prosecutors.

I use the word assault intentionally, as the defense…was more aggressive than any which I…had previously encountered (Gerstein, 2017).” Pity the prosecutor! It was the victims who were truly assaulted. FBI and court documents show that Acosta and his federal team not only caved under pressure but also actively worked with the defense to limit the charges.

Records show the prosecutors repeatedly yielded to Epstein’s demands and — even dodgier —strategized with the defense about how to settle the case with the least amount of public opposition (Levitz, 2018).